Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a group of structural heart defects present at birth, affecting millions of children worldwide. These anomalies range from minor issues that may require minimal intervention to severe, life-threatening conditions. Understanding CHD, its causes, diagnosis, treatment, and the emotional toll it takes on families is crucial for providing comprehensive care and support.

Causes and Types of CHD

CHD originates during fetal development when the heart does not form correctly. While the exact causes remain unknown in many cases, genetic factors, maternal illnesses, and environmental factors may contribute. There are various types of CHD, classified into two main categories: cyanotic and acyanotic.

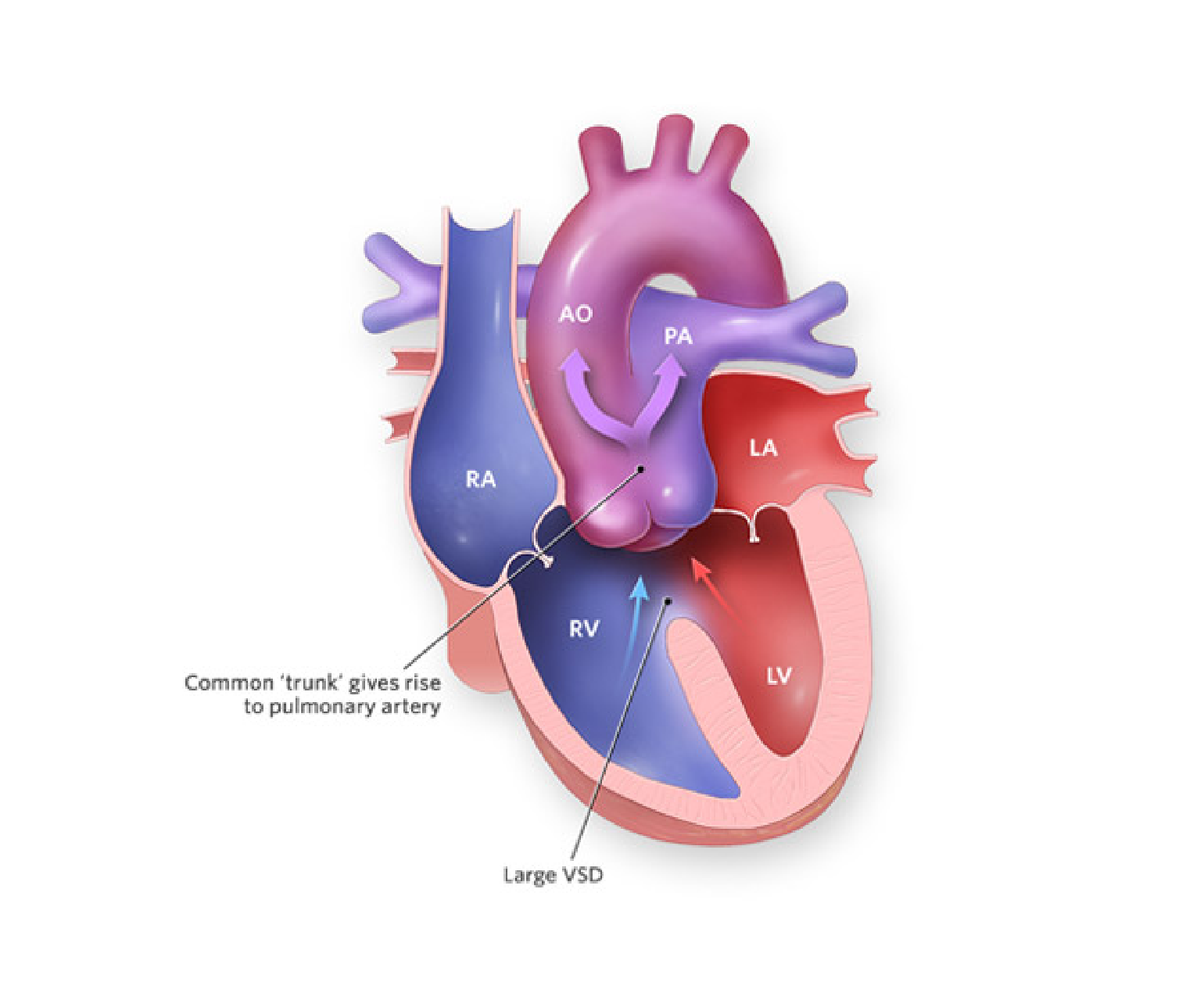

- Cyanotic CHD: These defects cause decreased oxygen levels in the blood, resulting in bluish skin and lips. Examples include Tetralogy of Fallot and Transposition of the Great Arteries.

- Acyanotic CHD: These defects do not lead to bluish discoloration but can still be serious. Examples include Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) and Atrial Septal Defect (ASD).

Diagnosis and Screening

CHD is typically diagnosed during pregnancy through routine ultrasounds or shortly after birth when a newborn is screened for congenital anomalies. Early detection is crucial for prompt intervention and better outcomes.

Treatment and Management

The treatment approach for CHD varies depending on the type and severity of the defect. Some children may only require periodic monitoring, while others need surgical or interventional procedures. Advances in medical technology and surgical techniques have greatly improved the outlook for children with CHD.

- Medication: Some CHD cases can be managed with medication to control symptoms and improve heart function. For example, diuretics may help remove excess fluid buildup, while beta-blockers can regulate heart rate.

- Surgery: Surgical intervention is often necessary for complex CHD cases. Surgeons can repair heart defects, replace damaged valves, or even perform heart transplants when required.

- Interventional Procedures: Minimally invasive procedures like catheterization can be used to treat certain CHD cases. These procedures involve threading a catheter through blood vessels to repair or correct heart defects.

Psychosocial Impact

CHD not only affects the child but also places a significant emotional and financial burden on families. Parents often experience feelings of guilt, anxiety, and stress. Siblings may feel neglected, and the child with CHD may struggle with self-esteem and body image issues as they grow.

Supportive care, counseling, and access to support groups can help families navigate these challenges. A multidisciplinary approach involving pediatricians, cardiologists, social workers, and psychologists is essential to address both the medical and emotional aspects of CHD.

Long-term Outlook

Advancements in medical science have led to a brighter outlook for children with CHD. Many go on to lead healthy lives with appropriate care and monitoring. However, long-term follow-up is critical to identify and address any potential complications as they grow.

Conclusion

Congenital heart disease in children is a complex and challenging condition that requires comprehensive care and support. Early diagnosis and access to specialized medical care are vital for improving outcomes. Equally important is the emotional and psychosocial support provided to families as they navigate the journey of caring for a child with CHD. With continued research and advancements in medical technology, the future looks promising for children born with these heart defects, offering hope for healthier and happier lives.